Today marks ten years since the devastating earthquake and Tsunami in northern Japan that caused one of the worst nuclear disasters in history. After a magnitude 9 earthquake hit off the coast of Tohoku, a massive Tsunami wiped off the Pacific coast in northern Japan, engulfing entire towns, killing over 18,000 people, and triggering a triple nuclear meltdown in the Fukushima Daiichi power plant.

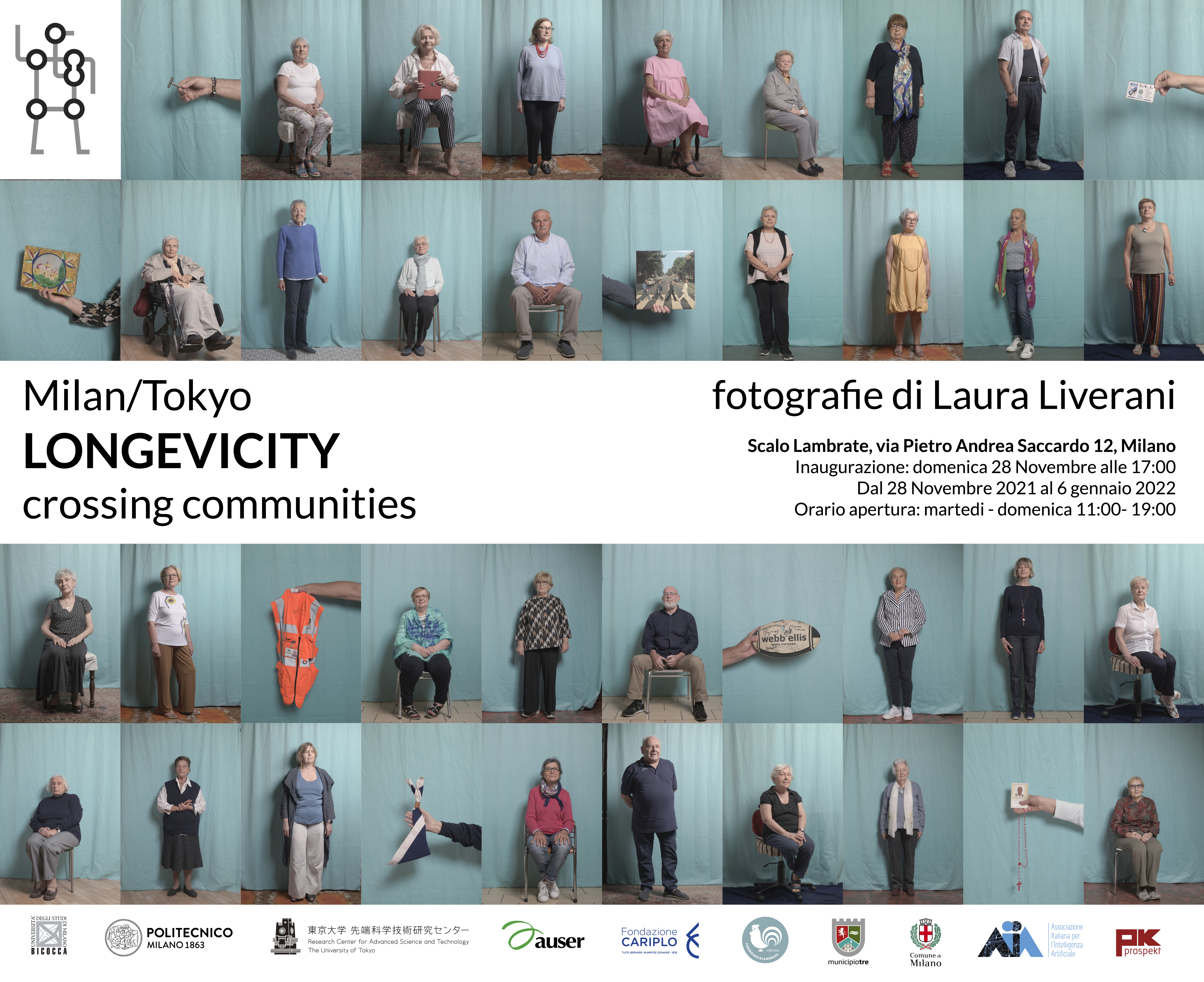

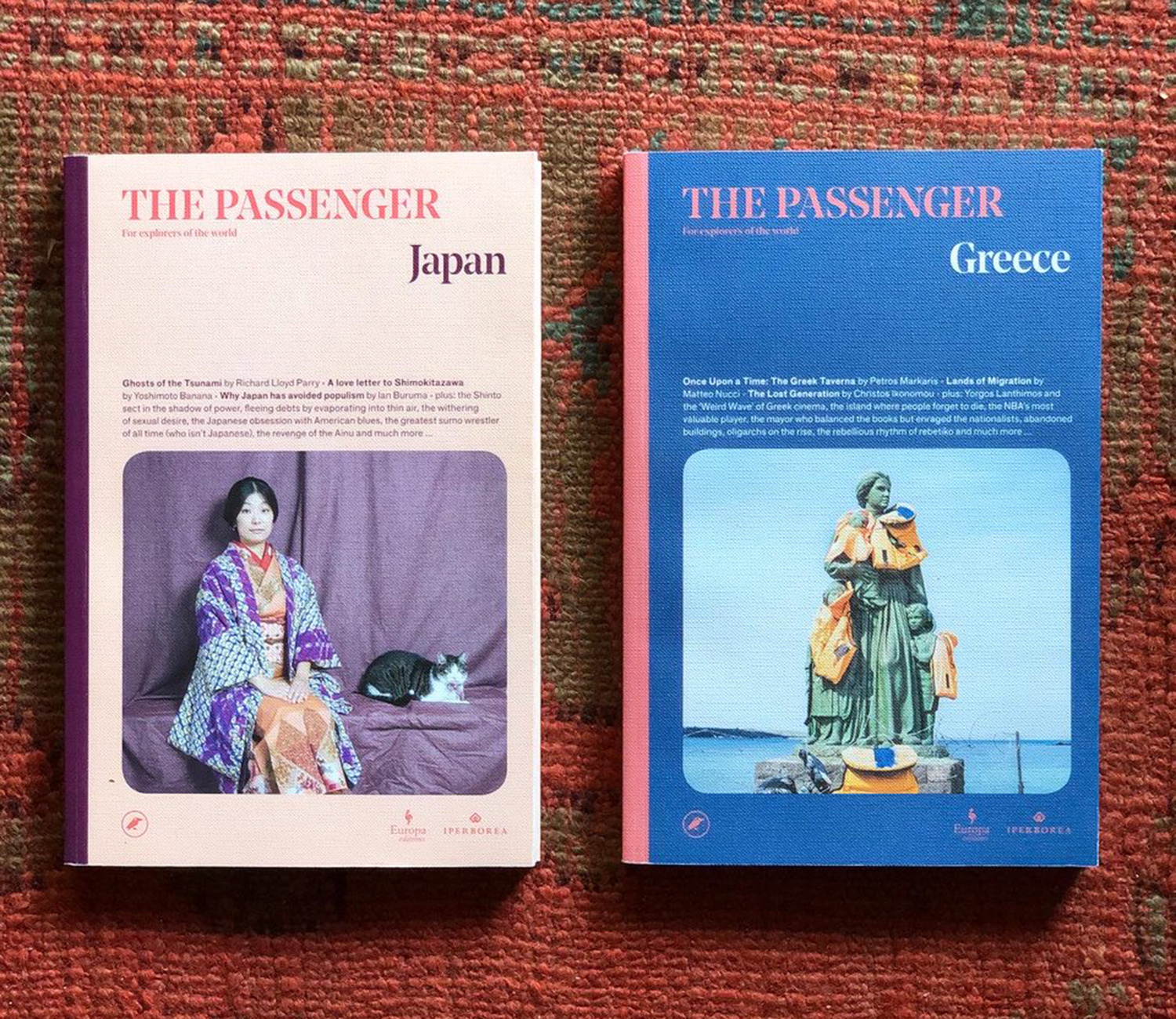

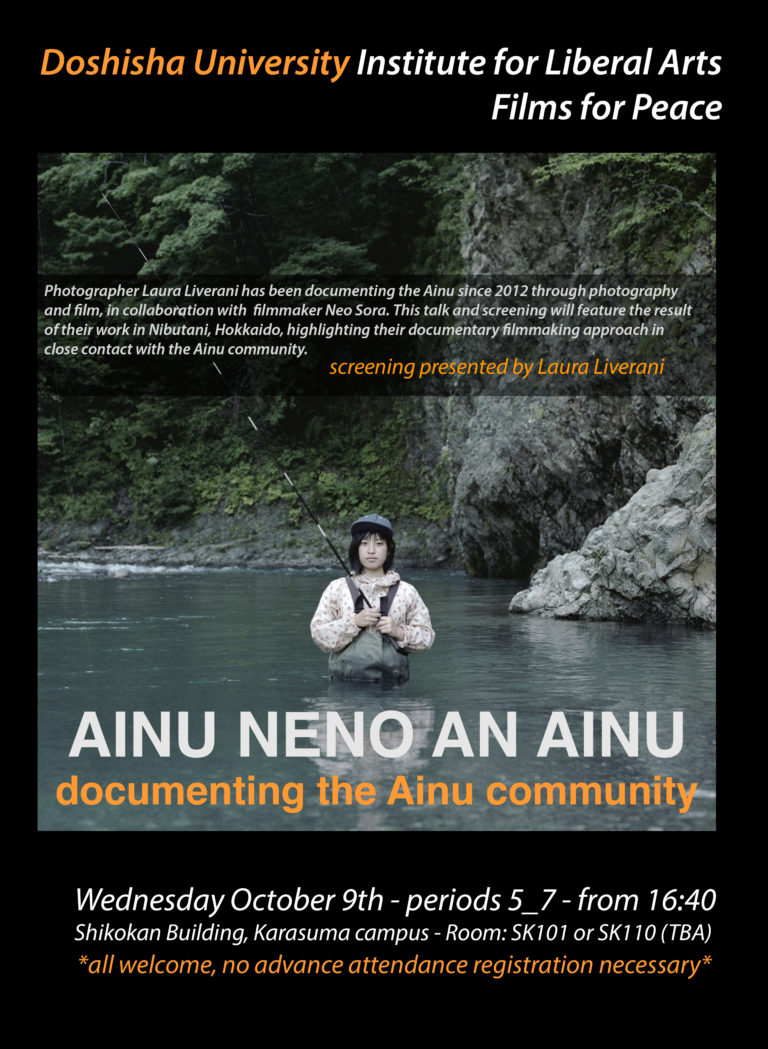

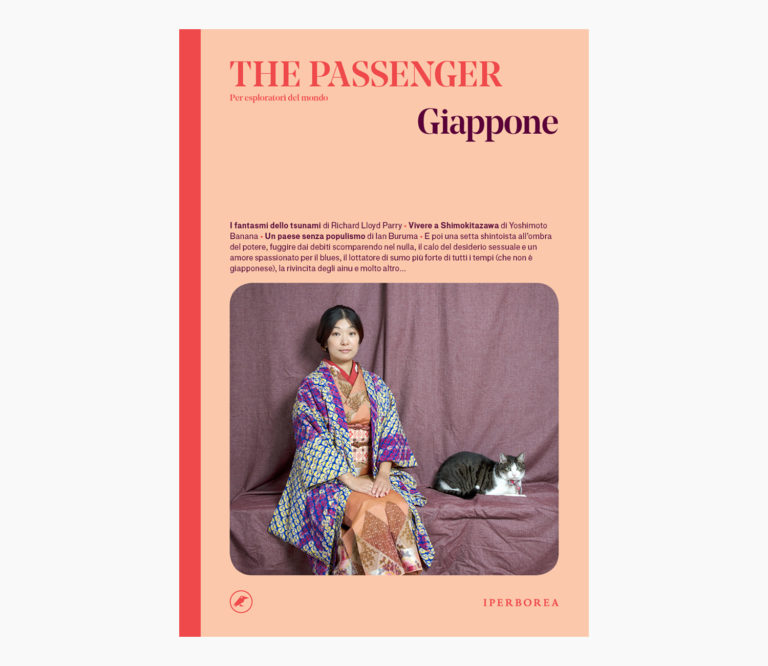

In September 2018 I was on assignment to illustrate Richard Lloyd Parry’s article Ghosts of the Tsunami for The Passenger – Japan. I decided to explore the affected areas by joining a friend, Sendai based architect Fumiko Yonemura, on a 3 day road trip along the Tohoku coast. She was going to meet her clients, and I would take photos. After many years, trauma was still tangible everywhere. We met her clients In Kesennuma: an elderly couple whose family-run fish manufacturing business had been wiped away by the Tsunami. After years, they were still operating in a converted container, waiting for Yonemura to complete the new fish factory project.

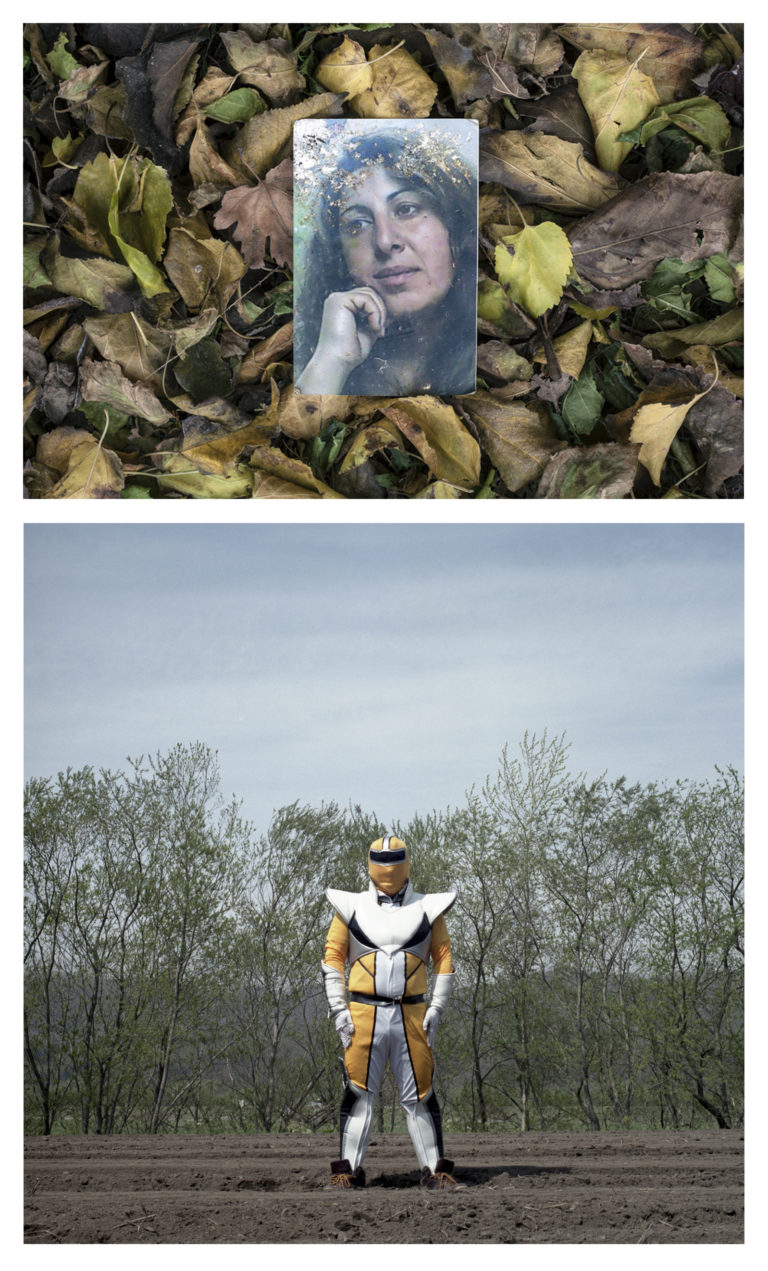

On the way to Kesennuma, near Ishinomaki, we stopped to gaze at a massive anti-Tsunami wall, emerging from an eerie, deserted landscape. Protective seawalls were constructed all along the Tohoku coast after the 2011 Tsunami. Now almost completed, the cement barriers, some as high as 14 metres, will extend for around 400 km along the coastline.

Not a single person I spoke to during the trip was in favour of the Bohatei, the seawalls. Most argued that they would not protect the coast in case of a massive scale Tsunami anyway. At best, the seawall will shield vacant land, as most inhabited areas by the ocean have been relocated several miles away. A resident spoke about an alleged economic interest in the seawall project from which lobbying construction companies would benefit. Most said that the seawalls not only ruin the landscape, but irremediably compromise the special bond the locals have formed with the sea for generations. “My son will grow up fearing the sea”, said an Iwate resident.